True Grit (1969)

No rhinestone cowboy.

Opinion: the best Westerns are high concept. “High concept” means you can pitch it easily. Think, “criminals are arriving at high noon to kill the sheriff,” or “three gunslingin’ dudes race to find hidden Confederate gold,” or “seven magnificent dudes defend a vulnerable town.” True Grit’s got that kind of pitch. Here it is: a girl’s father is murdered and she accompanies two wildly different lawmen to help her get revenge. Ooh, revenge. That’s good.

The precocious 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Kim Darby) hires Reuben “Rooster” Cogburn (John Wayne), the meanest U.S. Marshal in Arkansas, to track down her father’s killer. Tagging along with them is the vain Texas Ranger La Boeuf (Glen Campbell), who’s pursuing the same man for a different murder he committed in Texas.

Mattie hired Rooster because she heard he had “true grit,” but she worries it’s all talk. It must be, right? Rooster is a drunken fat old marshal who doesn’t show any moxie until the end of the film. But that end? When he takes on four men led by Ned Pepper (Robert Duvall) all at once?

ROOSTER: I mean to kill you in one minute, Ned. Or see you hanged at Judge Parker’s convenience. Which’ll it be?

PEPPER: I call that bold talk for a one-eyed fat man!

ROOSTER: [Pause] Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!

So he’s got true grit. And La Boeuf? He saves Mattie from her father’s killer, saves Rooster’s life, and then—with his last breath—saves Mattie from a pit full of rattlesnakes. He’s got true grit too.

Rating: 8/10, has true grit.

Cast and Crew

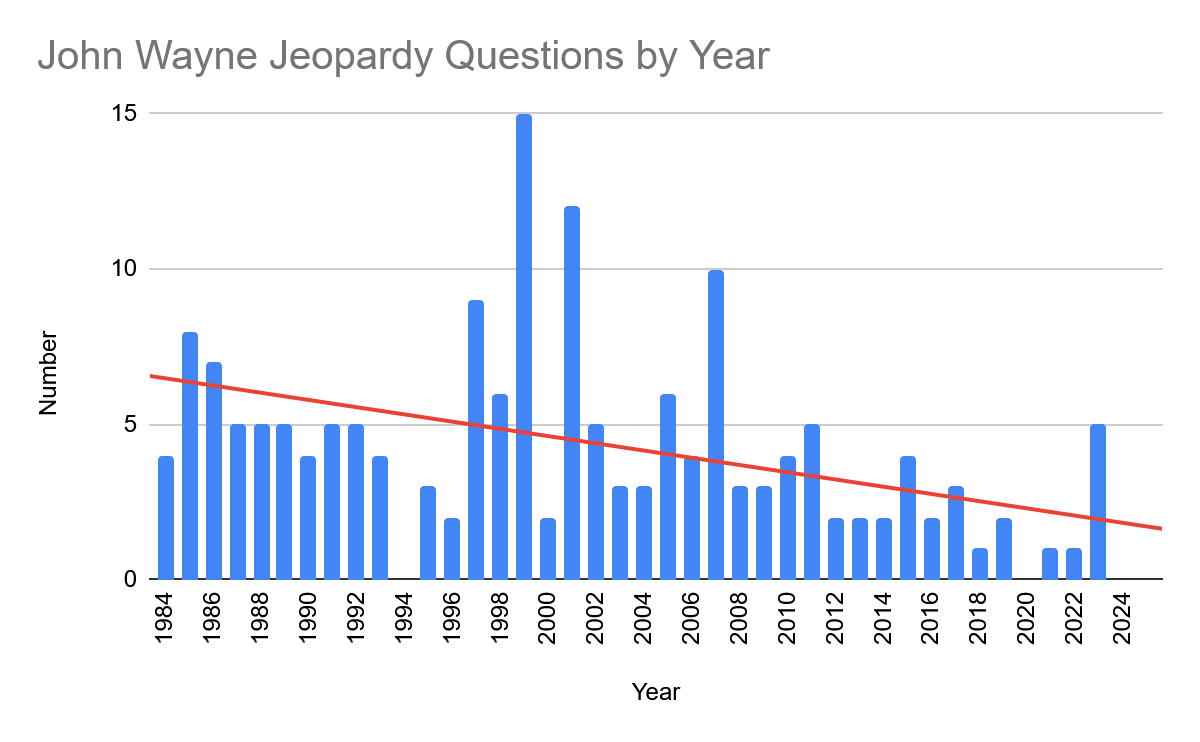

To write these posts, I often start by looking through the J! Archive database to get a feeling for what about each topic is “trivia worthy.” I noticed an interesting trend about John Wayne. Forty years ago, John Wayne was a guy you needed to know a lot about: his films, his family, his lore. Now? Well, not so much.

I could tell you this is cultural—that John Wayne’s representation of masculinity doesn’t speak to the American psyche today, that his views on minorities and homosexuals were regressive1, that his support of HUAC and the Vietnam War placed him on the wrong side of history—but it doesn’t have to be. John Wayne died in 1979 and there’s a natural fading that happens over time. Whatever it is, the upshot is that we won’t be covering every one of his movies “Jeopardy!” has ever asked about.2

On with it: John Wayne’s real name was Marion Morrison and he was nicknamed “Duke.” Before even discussing his movies, we should talk about his vibe. Wayne characterized acting as “reacting”: naturally responding to what was happening in the film. His dictum was “talk low, talk slow, and don't say too much.” His vocal patterns and physical mannerisms are extremely distinctive and you can see the boys on “Whose Line Is it Anyway?” riff on them here.

John Wayne played 142 leading roles.3 Which are the ones you just gotta know?

Stagecoach (1939). This one’s about John Wayne’s Ringo defending a stagecoach as it travels through Apache territory. It’s a Western from John Ford and the first he filmed in Monument Valley.

The Quiet Man (1952). This was the second of five films John Wayne did with Maureen O’Hara.4 It’s about an Irish-born American boxer who travels back to Ireland. It ends with a long, comic fistfight and was also directed by John Ford.

The Searchers (1956). John Wayne plays an Indian hunter searching for his abducted niece (played by Lana Wood as a child and Natalie Wood as an adult; the search took a long time). The line “that’ll be the day,” which Wayne says throughout the film, was repurposed by Buddy Holly into a chart-topping song. It was also directed by John Ford.5

The Man who Shot Liberty Valance (1962). We’ve talked about this one, including how it was directed by…well, you can probably guess.

John Wayne himself directed two films, both worth knowing. One was The Alamo (1960), about the titular Alamo; in it, he played Davy Crockett. The other was the pro-Vietnam War film The Green Berets (1968).

His final film, about a gunman dying of cancer (made while the real John Wayne actually was dying from cancer): The Shootist (1976).

The only one of these films I can really, really recommend is The Shootist. It takes all that John Wayne energy and reorients it, making it mortal. True Grit ends with Wayne hollering “come see a fat old man sometime!” and reasserting his virility by leaping a horse over a fence. The Shootist instead has Wayne telling Lauren Bacall, “I’ve been too proud to take help from anyone—guess I’ll have to learn.” To me, that’s a whole lot more interesting.

But there’s also John Wayne the symbol. The guy who can add gravitas by saying one line in The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) or give his imprimatur to what became the longest-running TV Western of all time (“Gunsmoke”). His name itself is a symbol, like in “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?” by Paula Cole (“Where is my John Wayne? / Where is my prairie song / Where is my happy ending?”) or in Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” (“Elvis was a hero to most / But he never meant s--- to me you see / Straight up racist that sucker was / Simple and plain / Mother f--- him and John Wayne”).

Glen Campbell goes toe-to-toe with Wayne in True Grit, despite being known primarily as a country music star. Campbell’s early hits followed the classic country move of putting the name of a city in your song: see “Galveston,” “Wichita Lineman,” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.”

Campbell was a big star in the ‘60s, but his two number one hits came in the 1970s: “Rhinestone Cowboy”6 and “Southern Nights.” The version of “Rhinestone Cowboy” from his final album is astounding, and made all the more poignant because he recorded it as he was suffering from Alzheimer’s.

Quick Hits:

Robert Duvall played Ned Pepper and got to call John Wayne a one-eyed fat man. We saw Duvall in his very first film role (he’s Boo Radley in To Kill A Mockingbird), but we’ll push off a larger discussion of him ‘til we see him in a starring role.

Dennis Hopper. He’s actually had supporting roles in two films we’ve watched—Giant and Cool Hand Luke (and was uncredited in Sayonara)—but 1969’s a huge year for him because it’s when Easy Rider, the film he wrote/directed/starred in came out. We’ll do a big Easy Rider run-down in our 1969 Wrap-Up.

Director Henry Hathaway was behind the camera for this one. Known primarily as a director of Westerns, Hathaway’s name doesn’t come up much at trivia, but “You Must Remember This” just covered him as part of their “The Old Man Is Still Alive” series.

The Trivia

True Grit takes place in the 1870s and La Bouef, Rooster, and Mattie’s father all fought in the Civil War. I figured we’d recap some of the key events in the run-up to that war.

From the founding of the United States up through the Civil War, we had tensions between slave and non-slave states. This led to an attempt during the Constitutional Convention to balance power between the two factions, including things like the three-fifths compromise (whereby the slave population gave the South extra representation in Congress and the electoral college).7

A crisis about slavery occurred as states were carved out of the Louisiana Purchase. There were 11 slave and 11 non-slave states when Missouri sought admission, meaning Missouri would tip the balance in the Senate no matter which way it went. The solution was the Missouri Compromise (1820): Missouri entered as a slave state but would be counterbalanced by Maine, which was split off from Massachusetts as its own state. Additionally, slavery would be banned north of latitude 36°30′ in the Louisiana Territory (except for in Missouri, which is north of that line).

States more or less came into the Union in pairs, one slave and one non-slave, to maintain the tenuous balance created by the Missouri Compromise. But after the Mexican-American War, a bunch of that “Spanish Territory” from the map above became America. The question: would that new land allow slavery or not? (Note that the Missouri Compromise didn’t answer that question.) One idea was the Wilmot Proviso (1846), which proposed banning slavery in the newly-acquired territory. Yeah, that idea was DOA.

Instead, what we needed was another compromise—this one was the Compromise of 1850, orchestrated by Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas and supported by president Millard Fillmore. In it, California entered the Union as a free state, and when Utah and New Mexico entered, they’d be given popular sovereignty to decide if they wanted slavery or not. (Though they wouldn’t become states for a while.) California was the 31st state, though, and 31 is famously an odd number, meaning the balance was tipped to non-slave states. To appease the South, the Fugitive Slave Law was passed, which required that escaped slaves be returned to their owners even if found in free states.

So we’ve saved the Union, right? Texas and California were states, the new territories would figure out slavery themselves, and the unorganized territory in the center of the country was bound by the Missouri Compromise. Or…was it? Enter the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Kansas and Nebraska needed to be states to facilitate the building of a transcontinental railroad. The Missouri Compromise suggested that those should both be non-slave states, but the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed both states to have popular sovereignty. The Democrats hoped this would put the slavery issue to bed (“look! it’s a state issue!”) but, uh, it didn’t work. Thus begins “Bleeding Kansas.”

Popular sovereignty incentivized people from out of state to come in to vote and cause trouble. A pro-slavery contingent (called “border ruffians”) came into Kansas, as did abolitionists (jayhawkers). Many jayhawkers carried “Beecher’s Bibles,” breech-loading Sharps rifles supplied by Henry Ward Beecher. John Brown, who later became real famous for his raid at Harpers Ferry, was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in Kansas. He and his sons murdered a bunch of people in the Pottawatomie massacre. John Brown is a complicated figure that this newsletter isn’t prepared to deal with.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act spelled doom for Franklin Pierce’s presidency. He’s actually the only sitting elected president who sought his party’s nomination and was denied it. James Buchanan became the Democratic nominee, won the presidency (he’s our only Pennsylvania president!) and, y’know, is now considered the worst prez of all time.

Yeah, we skipped over the Nullification Crisis and “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and the Republican party and Dred Scott v. Sandford and Abe Lincoln and probably a whole bunch of other stuff, sorry about that.

Odds and Ends

There was a sequel to True Grit called Truer Grit Rooster Cogburn (1975)…Charles Portis wrote the novel “True Grit,” and here’s a nice article on him from “The New Yorker”…Rooster describes lawyers as “pettifogging,” meaning “overinterested in petty details”…we didn’t really talk about Kim Darby, but man, she’s awesome in this film…John Wayne and John Wayne Gacy are totally different guys…Rooster says he married a “grass widow,” which is a term for a divorced woman…“you’ve done nothing when you’ve bested a fool.”

We’re not done with True Grit: we’ll eventually watch the 2010 remake of this film, as that iteration of the one-eyed fat man also got a Best Actor nomination.

This led to a 2020 attempt to rename John Wayne Airport in Orange County. 2020 feels like a long time ago, doesn’t it.

That includes: Sands of Iwo Jima (1949, Wayne was nominated for Best Actor), The Fighting Kentuckian (1949), Hondo (1953), The High and the Mighty (1954), The Conqueror (1956, he plays Genghis Khan???), Donovan’s Reef (1963), The Sons of Katie Elder (1965), El Dorado (1966), and Hellfighters (1968). We also won’t talk about his wife Pilar Pallete or his collection of kachina dolls or any of the other minutiae people once cared about from this one-time world-conquering Hollywood star.

Which was (according to this Final Jeopardy question from 2005) a Guinness record.

The others: Rio Grande (1950), The Wings of Eagles (1957), McLintock! (1963), and Big Jake (1971).

John Ford also did the “U.S. Cavalry trilogy” with John Wayne: Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950). Rio Grande isn’t the only “rio” film John Wayne did either: add in Rio Bravo (1959), Rio Lobo (1970), and Red River (1948). All three of those films were directed by Howard Hawks, the best-known non-John-Ford director of Westerns. Also note that “Rio Grande” and “Rio Bravo” refer to the same river.

The song was turned into the musical comedy Rhinestone (1984), a Dolly Parton–Sly Stallone bomb. That means “Rhinestone Cowboy” is one of an elite group of songs that were turned into movies.

In 1854, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison burned the Constitution and called it “a covenant with death and an agreement with Hell.”

Oof. You may have to revisit parts of this post after the end of Masters.