The Great White Hope is a fictionalized version of the story of boxer Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion of the world. As such, you’d think that this is a boxing movie. It ain’t.

Jack Jefferson (James Earl Jones) starts the film by winning the belt off of “the great white hope,” a retired titlist who has returned to the ring to prevent a Black man from becoming champ. When Jefferson wins, it puts a harsh spotlight on both him and his white partner, Eleanor Bachman1 (Jane Alexander). To “restore the natural order,” a bunch of evil government dudes go after Jefferson, eventually arresting him under the Mann Act.

Jefferson skips bail and bounces from London to Paris to Mexico, winning all his fights but finding that his skin color always makes him a target. The U.S. government eventually offers him a deal: if he takes a dive against the next great white hope, they’ll suspend his prison sentence. Elizabeth wants him to take the deal, but when Jefferson refuses, she throws herself down a well.

In the film’s climax, Jefferson agrees to the fight and, for ten rounds, he lets his opponent punch him around. Then, in the eleventh, after seeing a Black child in the crowd, Jefferson starts fighting back, dropping whitey to the mat a few times. But, in the last round, in a moment overwrought with the heavy symbolism that dogs this film throughout, Jefferson is knocked out, the end.

Rating: 4/10, not enough boxing in the boxing movie.

Cast and Crew

This’ll be the only leading role we’ll see James Earl Jones in2, so let’s take some time to discuss his storied career. In a “Simpsons” Lion King parody, viewers were treated to a shot of three of JEJ’s most iconic characters.

These roles were all made legendary through Jones’ deep, deep, deep voice. But his filmography goes beyond Star Wars (1977) and The Lion King (1994). Here are some more “oh yeah!” roles of his:

Coming to America (1988), where he plays the King of Zamunda, father of Prince Akeem (Eddie Murphy).

Field of Dreams (1989)—he’s the reclusive author based on J. D. Salinger.

All those ‘90s movies based on Tom Clancy books where his character is always some deep-voiced authority figure or whatever.

Cry, the Beloved Country (1995), an adaptation of the Alan Paton novel about South Africa in the run-up to Apartheid.

Yeah, we skipped over a lot3, including Conan the Barbarian (1982), where he plays villain Thulsa Doom and, uh, turns into a snake? And his film career might be matched by his stage career: he won a Tony for “The Great White Hope” and another for originating the role of Troy Maxson in August Wilson’s “Fences.” He also tackled some of theater’s most iconic roles, including King Lear, Othello, Hickey, Big Daddy, and Lennie.

But it’s that voice that really matters. If you don’t believe me, just watch him slowly, methodically, beautifully read the alphabet.

Quick Hits:

Hal Holbrook played one of the evil government dudes. He was in lotsa stuff over his long career, but his name typically Pavlovs to “Mark Twain Tonight!” a one-man show he did for over 60 years about, who else, Mark Twain.

Jane Alexander received an Oscar nod for The Great White Hope and later was nominated for All the President’s Men (1976), Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), and Testament (1983).

The Mann Act, also called the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910, was created to combat sex trafficking. It was later extended to apply to bringing women across state lines for “immoral purposes,” thereby criminalizing consensual sexual behavior. Bad act.

The Trivia

The sport of boxing goes back to antiquity, but our Trivia Section today starts with the codification of the Marquess of Queensberry rules in 1867. These rules added in some of the key elements of boxing, including gloves and counting to ten when someone is knocked down. The first heavyweight champ under these rules was John L. Sullivan4, the “Boston Strong Boy.” Sullivan only lost once in his career, but that single loss transferred the belt to James J. Corbett (“Gentleman Jim,” also known as “the man who beat the man”). Then, in an 1897 fight that was recorded, Corbett lost the title to Bob Fitzsimmons.

Okay, so we’re learning heavyweights: John L. Sullivan, “Gentleman Jim” Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons. Got that?

Flash forward to 1910. Four more men have been heavyweight champion, and two of those men—James J. Jeffries and the “Galveston Giant” Jack Johnson—are about to square off in the “Fight of the Century.” Jeffries had retired as champion but returned as the “great white hope” to take the belt back from Johnson. The fight ended with a Johnson TKO and a bunch of race riots.5

Jack Dempsey, known as “Kid Blackie” and “the Manassa Mauler” is the next guy you gotta know. He became champ in 1919 and defended his title five times, including against the “Wild Bull of the Pampas,” Luis Firpo.

Dempsey lost the title in 1926 to Gene Tunney, giving the excuse “I just forgot to duck.” Tunney and Dempsey then met in a rematch a year later in a bout remembered as “The Long Count Fight”: in it, Dempsey sent Tunney to the mat but didn’t go to a neutral corner so the ref didn’t start counting. Tunney stayed down for fourteen whole seconds without the fight being called. Later, Tunney dropped Dempsey and eventually won by unanimous decision.6

Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney—still good? Good!

Let’s get to the next “Fight of the Century”: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling II, 1938, Yankee Stadium. Max Schmeling became champ when he beat Gene Tunney. The belt then changed hands until it reached Detroit’s “Brown Bomber,” Joe Louis.7 Schmeling challenged Louis, looking to become the first person to win back the title. Louis himself wanted to avenge a 1936 loss to Schmeling—the first (and to that point, only) loss of his career. And for the fans? It was U.S.A. vs. Nazi Germany.

And…the Brown Bomber wins in the first round! U.S.A! U.S.A!

A reprieve if you’re tired of hearing name after name of long-dead boxers: Louis retained the title for 25 consecutive title defenses (a record for all weight classes) and had the longest single reign as champion of any boxer in history. 12 years being the baddest man on the planet—pretty good.

Then a flurry of names that come up sometimes. “Jersey Joe” Walcott! Rocky Marciano (the only heavyweight to end his career undefeated)! Floyd Patterson! Ingemar Johansson! Floyd Patterson again (the first heavyweight to retake the belt)! Sonny Liston!

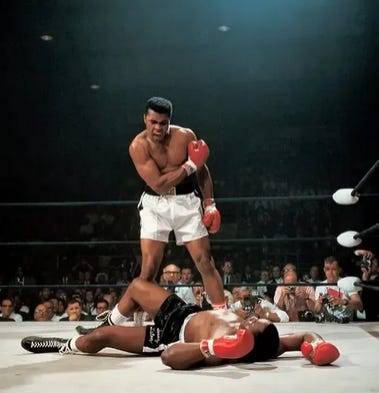

Wait a second…where have I seen Sonny Liston’s name before? Oh yeah.

Muhammad Ali (born Cassius Clay, also known as the “Louisville Lip”) took the belt from Liston in ‘64. Ali was already calling himself “The Greatest” before the fight8, but his legend only grew from here. Ali stayed undefeated, but in 1967 he was stripped of his title after refusing to be drafted (he said “I ain’t got no trouble with them Viet Cong”). Ali was found guilty of violating Selective Service laws and for three and a half years was unable to obtain a license to box. The U.S. Supreme Court eventually overturned his conviction, but during his time away from boxing, he became a symbol of civil rights, antiwar resistance, and uncompromising personal conviction.

And now, to our third and final “Fight of the Century”: Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier I, 1971, MSG. Ali had been champion but had been stripped of his belt. Philadelphia boxer Smokin’ Joe Frazier now held that belt. Both men were undefeated. And, in the fight, it was Frazier who emerged victorious, setting off probably the greatest four-year stretch of boxing history.

Frazier lost the belt in 1973 to George Foreman in “The Sunshine Showdown” in Kingston, Jamaica. (That’s the one with the famous call “DOWN GOES FRAZIER!”)

Hall of Famer Ken Norton faced Foreman in 1974 for the belt, losing in the second. Don’t sleep on Norton, though: he took on Ali twice in 1973, winning the first fight and breaking Ali’s jaw in the process, handing Ali his second-ever loss.

Ali and Frazier both wanted another shot at the belt, so they fought in ‘74 (“Super Fight II” at MSG) to determine who would face Foreman. Ali won.

That set up the 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire. It’s known for the chant “ALI BOMAYE” (meaning “Ali, kill him!” in Lingala) and Ali’s strategy of “rope-a-dope,” where Ali leaned back on the ropes and let Foreman exhaust himself throwing blockable punches.

With Ali the champ again, he had to defend his title in a third fight with Joe Fraizer. This one, the 1975 “Thrilla in Manila,” was another Ali victory. (Joe Frazier had only four losses in his whole career: two to Ali and two to Foreman. Darn.)

Ali lost the title in ‘78 to Leon Spinks but won it back at the age of 36 in a rematch.9 And if you think that’s impressive, George Foreman got the heavyweight title back in 1994, 20 years after losing it. With movies like Raging Bull and Rocky coming up, we’ll talk about boxing a bunch more.

Odds and Ends

This is director Martin Ritt’s third entry into this column, on the heels of Hud and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold10…a different Jack Johnson wants to make you banana pancakes…Cassius Clay was named after a white abolitionist from Kentucky…Howard Sackler wrote the play “The Great White Hope” and the screenplay for the film…in the film, when Jefferson can’t book a fight, he acts in a version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that’s somehow even more deranged than the one from The King and I…we won’t see James Earl Jones again in this column, but we’ll see his father, Robert Earl Jones, in The Sting (1973).

Postscript: For science, I watched episode 14 of season 7 of “The Big Bang Theory,” which revolves around Sheldon tricking James Earl Jones into coming to his “Sheldon-Con.” It was absolutely terrible, but whatever, I like JEJ.

A composite character based on a few of the real Jack Johnson’s wives.

Though we’ve already seen him once—he’s briefly in Dr. Strangelove.

We cut out basically the whole ‘70s, but here’s a snapshot: The Man (1972), where he’s the first Black president; Claudine (1974), which scored his co-star Diahann Carroll an Oscar nod; The River Niger (1976), an adaptation of a Tony-winning play; and The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976), a movie with an all-time great name.

Sullivan was also the last champion under the London Prize Ring Rules, which covered bareknuckle boxing and which were superseded by the Marquess of Queensberry rules.

This was followed by the events of the film: Johnson was targeted by the government for violating the Mann Act, he fled the country, and eventually he lost the belt to Jess Willard in what Johnson claimed was a rigged fight. Johnson eventually returned to the U.S. and served his prison sentence at Leavenworth. President Trump posthumously pardoned him in 2018.

Tunney claimed he could’ve gotten up sooner and Dempsey believed him, so it’s not a crazy scandal or anything. Still, when a fight gets a cool name, you should remember it.

Passing through James J. Braddock, “Cinderella Man” (played in a 2005 film by Russell Crowe).

And he could back it up: he was already a light heavyweight gold medalist, having won the event at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Ali allegedly threw the medal he won into the Ohio River after facing discrimination back home.

We won’t mention Ali’s ‘80s fights with Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. Also, here’s a handful of other guys to know in conjunction with Ali: cornerman Drew “Bundini” Brown, who coined the phrase “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee”; trainer Angelo Dundee; promoter Don King; and broadcaster and famous friend of Ali, Howard Cosell.

Wait, the guy who directed the stark, sweeping beauty of Hud directed this inert lump? Weird.

That particular episode of The Simpsons features not James Earl Jones, but Harry Shearer doing an impersonation (of all characters). https://simpsons.fandom.com/wiki/James_Earl_Jones