It starts with a meet-cute. He’s Oliver Barrett IV (Ryan O’Neal), a BMOC Harvard boy. She’s Jenny Cavilleri (Ali MacGraw), a Radcliffe music major with a foul mouth. Her family’s working-class and he grew up in a mansion, but no matter—the pair fall in love and marry. Then she dies.

The story isn’t all “cute girl dies,” though—first there are some rote challenges for the couple to overcome. The main one is posed by Oliver’s father, Oliver Barrett III (Ray Milland), who wants his son to marry someone of higher status. The son ends his relationship with the father, inspiring a big fight between Oliver and Jenny. When Oliver tells Jenny he’s sorry, she says the line everyone remembers from the movie: “love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

But still, we’re on a collision course with that unhappy ending. Jenny goes to the doctor when having trouble conceiving and discovers that, yep, she’s dying.1 Then she dies. Afterwards, outside the hospital, Oliver sees his father. They reconcile, and when his father apologizes, Oliver tells him “love means never having to say you’re sorry.”

Rating: 6/10, didn’t love it, sorry.

Cast and Crew

Love Story was a phenomenon. When watching the film, it’s hard to see why, but maybe The Notebook (2004) is a good analog: a weepy, maudlin tale of love between two good-looking kids played by actors on the verge of stardom. Or maybe not, but I’m just trying to make sense of how Love Story was the highest-grossing film of 1970. That’s nuts.

Anyway, Ali MacGraw was one of those two good-looking kids. Before Love Story, she only had one starring film role to her name.2 She was married to producer Robert Evans, though, and Evans bought the screenplay for Love Story as a vehicle for McGraw. After Love Story, she was one of the biggest stars in Hollywood.

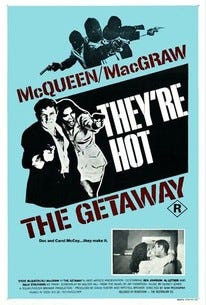

So what did she do with the stardom that comes with being a cute, preppy girl? She zagged: her next film was The Getaway (1972), a Sam Peckinpah movie about a bank robbery. Peckinpah’s desperate, nihilistic movies don’t do anything for me, but man, if you thought MacGraw and O’Neal were hot, MacGraw and McQueen are, like, way hotter.

The Getaway might be best remembered because the leads began an affair. MacGraw divorced Evans and married McQueen, then didn’t make another film until the 1978 Peckinpah film Convoy.3 But her moment had passed and the rest of her career was basically a footnote.4

Like Ali MacGraw, Ryan O’Neal came into Love Story as a budding star and came out a supernova. O’Neal was already known to audiences from his 501-episode run on the TV version of “Peyton Place,” that sexy, dumb show about a town full of secrets.5 After Love Story, he wouldn’t have to go back to TV for twenty years.

One highlight of his post-Love Story6 was playing a con man in Paper Moon (1973), a Peter Bogdanovich film. That film co-starred his real-life daughter, Tatum O’Neal, who became the youngest winner of an Oscar.

O’Neal also starred in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975).7 Despite being well-considered now, it was a flop when it came out and hurt O’Neal’s career. Even though O’Neal worked through the 2010s (he was on “Bones,” playing the lead character’s dad), there just aren’t many more titles of his you need to know.8 But, like MacGraw, O’Neal had a high-profile relationship, his with Farrah Fawcett.

Ray Milland crushes his role as Oliver’s disapproving father. The hold on his face after he learns Jenny has died is beautiful.

Since we began this project with the films from the 1950s, that means we missed Milland’s Oscar-winning turn in Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945). Whoops. That’s probably a pretty good movie. We also haven’t mentioned that he’s the dude in Dial M for Murder (1954) who’s trying to murder Grace Kelly. That’s probably a pretty good movie too. Put “Ray Milland film festival” on the list of stuff we should do.

The Trivia

Oliver’s last name is “Barrett,” and when Jenny meets him, she asks “Barrett like the poet?” Moreover, when the pair get married, Jenny reads Sonnet 22 from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sonnets from the Portuguese.” Let’s do a bit on Robert Browning and EBB.

But first: what’s a sonnet? The form originated in Italy in the 13th century. Its name comes from the Italian sonetto, “little song,” as many early examples were intended to be sung. In form, a sonnet is a 14-line poem written in a specific rhyme scheme and often in iambic pentameter.

There are two main types: the Petrarchan (or Italian) sonnet and the Shakespearean (or English) sonnet.9

The Petrarchan sonnet divides into an eight-line octave (typically rhyming ABBAABBA) and a six-line sestet (which can vary—e.g., CDCDCD or CDECDE). The division between the octave and sestet often includes a shift in tone called the volta, literally “turn.”

The Shakespearean sonnet instead uses three four-line quatrains followed by a two-line couplet at the end—so ABBA CDDC EFFE GG.

Okay, to the poets themselves. Who was Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)? Well, she came from a family of means and was a precocious child who wrote constantly. While she was young, she developed a disease that made her a “semi-invalid” and for which she took laudanum and morphine for the rest of her life. She lived much of her life at Wimpole Street10 under the care of her domineering, possessive father.

And then: her relationship with Robert Browning. Browning wrote to Barrett after reading her 1844 work “Poems,” and soon they were married in secret (because her father disapproved—oh hey, just like in Love Story!) and moved to Italy where they lived in the Casa Guidi.

Look: sometimes “Jeopardy!” will want you to know an EBB poem11, but more often than not, your Pavlov is “lady poet from the mid-1800s” or “poetess whose husband was also a famous poet” or “lady sonnet writer.” This underplays her work: during her life, she was so prolific and so well-regarded that, after the death of poet laureate William Wordsworth, she was considered for the position. Here are two works you gotta know:

“Sonnets from the Portuguese.” This group of poems got its name from Robert’s nickname for Elizabeth, “my little Portuguese.” In one telling, Elizabeth believed the poems were too intimate and pretended that they were translations of existing poems that had been written in Portuguese. The collection includes Sonnet 43, which is the one that begins “How do I love thee? let me count the ways.”

Those sonnets are at least somewhat readable. That contrasts to “Aurora Leigh,” a book-length poem about an orphaned Englishwoman who becomes a poet.12

Okay, that’s Elizabeth. What about Robert Browning (1812–1889)? RB wasn’t one of your whiny lovesick poets. EBB wrote about how many ways she loved (FYI, it’s nine ways); RB wrote “My Last Duchess,” about a Duke who for sure murdered his wife.13 I prefer the murdering Duke poem.

Here are some more to keep in mind:

“The Pied Piper of Hamelin,” based on the 1284 legend of the Pied Piper. The musician with the colorful clothes is hired to remove rats from a German town. He does, the town stiffs him on payment, and the piper leads 130 of the town’s children to their death.

“Pippa Passes,” about a silk-winding girl in Asolo, Italy, on New Year’s Day, which happens to be the one day off she gets a year. It’s known for the line, “God’s in his heaven— / All’s right with the world!”

And then a handful of other poems with quotable lines:

“Andrea del Sarto,” about an Italian painter, has the line, “Ah, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp, or what’s a heaven for.”

“Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”: it gets its name from “King Lear” and provides the basis for Stephen King’s “The Dark Tower” series.

“Home Thoughts from Abroad” finds Browning writing, “Oh, to be in England now that April’s there.”

“Rabbi ben Ezra” contains the line “grow old along with me, the best is yet to be.”

Odds and Ends

The question we ask for every Boston movie: how would it be if Mark Wahlberg played the lead? (fine, probably)…“everybody [drives like a maniac] in Boston”…when Jenny introduces herself as “Cavilleri,” Oliver’s family asks “As in ‘Cavalleria Rusticana’?”, the opera from Pietro Mascagni…Henry Mancini did the (pretty good) “Theme from ‘Love Story’”…this is Tommy Lee Jones’ film debut…we’ll see actor John Marley again in a 1972 film where he’s in bed with a horse…the Brownings had one son: Robert Barrett Browning, whom they called “Pen”…Erich Segal, author of the novel “Love Story,” wrote the film’s screenplay…Arthur Hiller, a director known for his collaborations with screenwriters Neil Simon and Paddy Chayefsky, directed; we’ll see his work again in this column.

…there’s no way there’s a sequel to Love Story, right? Right? Right?! WRONG. Bring on Oliver’s Story (1978). Unsurprisingly, Ali MacGraw wasn’t in it and it was not a success.

CORRECTION: In last week’s post, we stated that James Earl Jones voiced “Bleeding Gums” Murphy, Mufasa, Darth Vader, and the “This Is CNN” guy in the Simpsons episode “‘Round Springfield.” Wrong—Murphy was voiced by Ron Taylor and the JEJ impersonations were done by Harry Shearer. D’oh! Thanks to Myron for the catch.

Though the film doesn’t say exactly what she’s dying from, they do mention it’s a blood disease. The symbolism is obvious: he’s a blue blood, she’s dying because she’s not one.

That was Goodbye, Columbus (1969), a film based on a Philip Roth novella.

Another entry into the “movies based on songs” canon.

Other McGraw works: the films Players (1979) and Just Tell Me What You Want (1980); turns on the miniseries “The Winds of War” (1983) and prime time soap “Dynasty”; a yoga video that helped spark the popularity of the practice.

Based on a sexy, dumb movie, which itself was based on a sexy, dumb book.

Meaning we won’t talk about 1972’s What’s Up, Doc?, a screwball comedy he co-starred in with Barbra Streisand. I watched that movie and thought Ryan O’Neal was Peter O’Toole the whole time. I don’t know if that says more about Ryan O’Neal or me.

Here’s what we wrote about Barry Lyndon when discussing Kubrick: “Barry Lyndon is based on a William Makepeace Thackeray novel and it’s another Kubrick film hipsters say they like even though they don’t. The film is basically Tom Jones if Tom Jones wasn’t funny.”

A Bridge Too Far (1977), maybe? Or The Main Event (1979) with Barbra Streisand again, a film about boxing?

Note that Petrarch dedicated many of his sonnets to Laura while Shakespeare’s sonnets were to an unnamed fair youth and the dark lady.

Wimpole Street provides part of the name of a 1930 play by Rudolf Besier called “The Barretts of Wimpole Street.” There are two film adaptations: one from 1934 with Norma Shearer and Fredric March as the couple and Charles Laughton as Elizabeth’s imperious father; the second from 1957 with Jennifer Jones and Bill Travers as the couple and John Gielgud as the father.

e.g., “The Sleep,” “The Soul’s Expression,” “A Vision of Poets.”

In a fit of legendary cattiness, translator Edward Fitzgerald wrote that EBB’s 1861 “death is rather a relief to me...no more Aurora Leighs, thank God.”

The poem has a Duke describing a portrait of his late wife (“That's my last Duchess painted on the wall, looking as if she were alive”) to his prospective new wife’s emissaries, and it’s got red flags galore. The poem is based on the real Duke of Ferrara and his dead wife Lucrezia de’ Medici.

Interesting that the movie doesn't give Jenny's cause of death...it's clearly leukemia in the book. I had to check that on Wikipedia and was rewarded with the knowledge that the Oliver character was based on both Al Gore AND his Harvard roommate, Tommy Lee Jones. There's some trivia for you.